Fearing for My Life and Doing It Anyway: A 4-Day Road Trip Through Salta and Jujuy, Argentina

A story told from Jenna's perspective of our road trip adventure through the Salta region of Argentina.

STORYGUEST POST

Jenna Cartusciello

3/30/202523 min read

It’s nighttime on a cliff-side mountain road in Argentina. I’m in the middle seat of a tiny white Nissan, crammed in with four people I met a week ago. The Nissan has a huge, spider-like crack spreading across the driver’s side of the windshield, and the car’s interior perpetually smells like fart. On another hairpin curve where the cliffside dissolves into total blackness, we pass an overturned semi-truck on the side of the road. It must have crashed into one of the very few guardrails, failing to make the turn. I’m crying as quietly as I can. I don’t wipe my face, worried that someone will see the movement and turn to look. Gabi, the girl on my right, notices anyway. She passes me her neck pillow shaped like a shrimp, and I hug it, my tears raining onto the mottled orange fabric. There is no end in sight to this pitch-black, rail-free, switch-back mountain road. I’m in my special kind of hell.

As a novice traveler with a fear of heights, I should have researched the Salta Province before I signed up for a four-day road trip there. Yet every time I recount this story to friends and family, I still say I had the time of my life.

Part I: How I Got Here

I wound up on that treacherous mountain road because of a decision I had made a year earlier. In January 2023, I joined WiFi Tribe: a paid-membership-based community that hosts month-long trips in beautiful locations worldwide. Each trip holds between 10 and 20 digital nomads, or people who travel and work remotely, and members pay roughly a month’s rent to book a room in a shared house or apartment.

I signed up out of fear that life was passing me by as I spent each day alone, working from home. However, it took me a full year to book my first trip. I was nervous about flying solo and worried I would be out two grand if I didn’t enjoy it. But in December of that year, I finally bit the bullet. I chose the Buenos Aires trip for January 2024 because it was one of the more affordable options (and because it was my last chance to use the $500 I had spent on the annual membership).

That first week blew me away. The sprawling, vibrant city was full of sunny cafes and dog walkers in the mornings, and in the evenings, the scent of carne asada and the rhythmic thump of club music. The people I was staying with were the best part. I found myself making instant bonds with many other WiFi Tribe members, all of whom were spread across three apartments in close proximity. I surprised myself by shedding my sweatpants, slippers, and nighttime doomscroll in favor of skirts, sandals, and $5 salsa classes with new friends.

And so, when a few members suggested a weekend trip to the Salta province, I said yes. I had never heard of Salta, the Humahuaca mountain valley, or the Rainbow Mountains. I’m from New Jersey; I didn’t even know what a salt flat was. But those first few days in Buenos Aires had already changed me, and my secret, adventurous spirit had reared its head in the form of raging FOMO. I couldn’t miss it.

Part II: Salta City

By Wednesday of that week, I had sent Gunnar—a guy I’d met five days ago—all of my personal information and a picture of my passport so he could book the flights and hotels. On Thursday, I packed a single duffle for four days. (A more seasoned Triber, Daniel, gawked at me when I initially told him this was impossible.) Come Friday, my roommate Sheenal and I were clambering into an Uber to meet Gunnar and two other Tribers, Stacy and Gabi, at the airport.

Our trip through the tiny, crowded airport was relatively smooth, and the flight from Buenos Aires to Salta was fast. In trying to grab a taxi that would take us to a car rental agency, we hit our first snag. We wanted to take one big cab together, but the largest car available had only five seats, a very slim trunk, and a driver insisting we and all of our bags would fit. We opted instead for two cabs and split up—Sheenal and I in one, Stacy, Gunnar and Gabi in the other. Gunnar sent Sheenal the address and a photo of the agency and told us not to enter the building if we got there first.

Thirty minutes later, our driver pulled up on a side street that looked nothing like Gunnar’s photo. A note of panic entered my voice as I told the driver in terrible Spanish that this was the wrong address. (Were we about to get murdered?) We pinged the group chat to ask if we were on the right route.

Gunnar apologized and sent us the correct address.

Fortunately, we weren’t far off and arrived at the agency a little after 11 p.m. The street was deserted and the brick building was small, with a narrow garage beside it. The door was open, and the metal security gate covering it was partially closed. Sheenal and I approached the gate as our taxi drove away. We saw a man sitting behind a desk in a barren room with fluorescent lights and lime-yellow walls. (Were we about to get murdered?) He looked up and asked, “Gunnar?” Sheenal nodded, and we decided it was better to be in the yellow room than the dark, deserted street. We stepped inside and waited by the door.

Five minutes later, the rest of our crew arrived. “I thought I told you not to go in without me!” Gunnar scolded. Sheenal and I protested that the street seemed worse. Over the next 20 minutes, Gunnar and Gabi worked through the rental agreement with the agent using a mix of Spanish and English. It was past midnight when the agent led us through a side door into the dark garage (were we about to get murdered?) to inspect our rental. We quietly took photos of a giant crack in the windshield and various other scratches and marks on the car’s exterior. Then Sheenal and Stacy opened the passenger doors.

“Ugh!” they exclaimed, stepping backward. The smell of something old and forgotten wafted out of the car and filled the garage. We dumped our bags into the trunk and clambered in any way; we needed to get to our hotel, find food and sleep. I volunteered to take the middle seat, so Gabi sat on my right and Sheenal on my left. Stacy gave directions as Gunnar pulled out of the garage and onto the road. We theorized the source of the smell on the way (spilled milk? ancient cabbage?) and Gunnar blasted the A/C to help clear it. Gabi called the car a “fart wagon” and the name stuck.

One steak-heavy, midnight meal later, we walked back to our five-person hotel room in the Salta city center, giddy with fatigue and newfound comradery. Sheenal and I opted to share the large bed in the side room while Gunnar, Stacy and Gabi debated the best way to arrange themselves on three twin beds lining the main room. (Which person would have their head next to someone’s feet?)

As I lay in bed waiting for sleep, I couldn’t help but smile. I had flown on a whim to an area of the world I had barely researched, and I had let people I didn’t know make the itinerary. I hardly recognized myself.

Part III: Parque Nacional los Cardones

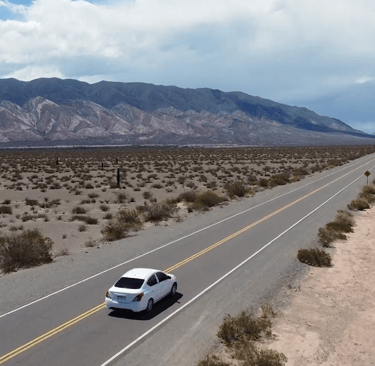

After a quick breakfast in Salta at a local café (toast, instant scrambled eggs, tiny strips of bacon, and a sprinkle of sesame seeds), we hit the road. We set out for Route 33, which stretches across Parque Nacional los Cardones, or Los Cardones National Park. Smooth highways and two-story buildings gave way to dusty roads and farm lands as Sheenal, Stacy and I took turns playing car DJ with the AUX cord.

By the time we reached the entrance to the national park in Chicoana, my butt was sore and my stomach unsettled by the bumpy road and gas-station chocolate. But it didn’t matter. Los Cardones National Park was more beautiful than I could have imagined. The road sliced across flat plains, with green, orange and pink mountains rising in the distance. Then it wound upward through a mountain range covered in lush greenery. The higher we climbed, the cloudier it became, with a thick fog spreading from the peaks into the valleys.

I stayed in the middle seat after every pee break despite my friends asking if I needed to switch. Something about being far from the edges of the car made me feel safer around the hairpin turns, which were becoming more formidable.

Up and up we drove, passing several huts advertising tortillas, empanadas and more, though they were all abandoned. After multiple stomach-dropping switchbacks, we reached one of the main viewpoints on Route 33: “Cuesta del Obispo,” or Bishop’s Slope. It stood 3,240 meters (10,630 feet) above sea level overlooking two valleys. We took our time soaking in the view.

In the visitor’s center, two men were selling handmade trinkets. I bought a small clay whistle and annoyed the group for a few minutes as I learned to play. We watched a coyote cross the road.

Back on Route 33, I braced myself as Gunnar drove us around a few more hairpin turns. Then, my anxiety settled into the background as the road flattened out. The vibrant green plants gave way to dry, desert-like terrain, and five-foot-tall cacti loomed among the rocks and shrubs. We stopped to take photos, posing with the cacti and wild llamas. Finally, we reached the end of the park and entered an area called Payogasta.

Part IV: Route 40 Fiasco

After another break, we turned onto Route 40 and headed north, hoping to take this scenic route to our Airbnb in a town called Purmamarca. It had been over four hours since leaving Salta, and our road snacks had dwindled. Sheenal and I pulled out our phones and began researching restaurants whenever we had cell service. There was just one problem: The restaurants nearby were either closed or non-existent. One turned out to be a tiny farmstand selling herbs.

We decided to continue up Route 40 for another hour, hopeful that a town called La Poma would have an open restaurant. The dusty road had turned to gravel, and Gunnar occasionally veered around potholes. My brain rattled around in my head as the conversation in the car subsided and everyone focused on finding food. Our tiny Nissan left a continuous stream of dust in its wake.

At last, we turned off the main road and took a fifteen-minute drive around a cavernous red-rock valley to La Poma. A stray donkey trotted in front of our car, then peered through the window as we navigated around him.

Doubt crept into my mind as we drove into the town center. It was deserted except for the occasional local, who gaped at us as we drove past. We parked by the building marked on the map as the restaurant, “Comedor y hospedaje El Acay,” and walked up to the main door. We knocked. Silence.

We stood on the empty street, debating our options. We were nervous about driving well into the night without food. Then, we noticed a woman walking toward us. We waved, and she waved back. She came to the entrance holding a key, and Gunnar and Stacy asked in Spanish if the restaurant was open. She shook her head no. They talked to her a bit more, and she led us inside anyway.

The small dining room had sturdy, homemade wooden tables and chairs. The woman, whose name was Margarita, went into a back room and brought out her husband, Miguel. They looked at us.

“Omelets?” Margarita asked.

“Si!!” we exclaimed in unison.

“Empanadas?”

“Si!!”

“Ensaladas?”

“Si!” we said, though with a little uncertainty this time. (Was fresh produce safe to eat in this area of Argentina?) Margarita nodded, and she and Miguel went back into the kitchen.

As we ate our fresh empanadas and omelets, leaving the salad untouched, we wondered if we’d be able to make it from La Poma to our Airbnb in Purmamarca, which would be about five more hours of driving on Route 40. Gunnar asked Margarita about this when she returned, then relayed his intel.

“She says we can’t drive on Route 40 unless we have a car with four-wheel drive,” Gunnar said. We all exchanged looks, thinking of our tiny yet faithful Nissan. If we couldn’t get through on Route 40, we would have to go back through Los Cardones National Park and Salta City to reach Purmamarca.

We paid for the food with our dwindling cash and stepped back outside, thanking Margarita and Miguel as we left. Gunnar then drove us over to the police station in town, per Margarita’s instructions, to ask about Route 40. He spoke with a friendly officer while we waited inside the car.

“Bad news, guys,” Gunnar said after returning to the driver’s seat. “The officer said the road is flooded, and we won’t be able to get through in our car. She was talking about a couple of big rivers.” Feeling defeated, we made our way out of La Poma, back around the cavernous red-rock valley. We turned right on Route 40, heading back to Route 33 through the national park. Suddenly, Gunnar slowed down.

“So, we’re not gonna make it to Purmamarca in time to check in if we go all the way back to Salta,” he said.

“...Right,” Stacy said.

“Why don’t we just try Route 40? We’ll have to stop somewhere else tonight anyway. Why not try to make it through?”

I felt a spark of panic in my gut. No. Nope. No, I thought. A police officer had told us we couldn’t do it, which was all the proof I needed. What if we got stuck in a river with no service? (Were we about to die?) Sheenal and Stacy agreed with Gunnar’s plan, then Gabi did, too. I silently accepted my fate as Gunnar turned the car around.

Then, I decided to embrace it. What was life without a little life-threatening adventure? I pulled out my phone and scrolled through the downloaded songs in my iTunes, since we had no service for Spotify, and put on “Eye of the Tiger.” There was a collective sound of appreciation as everyone bobbed their heads to the beat. Gunnar hit the gas, and we raced down the road, gravel and dust flying.

BOOM.

One of the wheels hit a pothole and the car bottomed out. I clutched Sheenal’s and Gabi’s knees, instinctively bracing myself. Gunnar slowed to a stop, then got out to check the car.

A few moments later, he was back. “Everything looks okay!” he said, relieved.

“Maybe…maybe we don’t play ‘Eye of the Tiger’ right now,” Stacy said. We laughed nervously, and I switched the song.

Fifteen minutes later, we came to our first obstacle: a puddle that covered at least 30 feet of road with tall grasses on either side. We all hopped out of the car and analyzed the puddle. In an attempt to measure its depth, Sheenal found a long branch and tried to stick it in the center. The branch fell in. After about 15 minutes, a woman on a motorbike came around the bend. We watched as she drove on a slant around the side of the puddle into the grass, passing it with ease. We stared at her, then got in the car and tried the same thing. We made it around with no issues.

Laughing at our 15-minute-long puddle analysis, we drove onward and paused at a tiny brook carved through the road. Gunnar carefully drove over it. “Maybe to them, a river isn’t really a river,” he said thoughtfully. The next break in the road, a stream with steady flowing water, posed a more significant challenge. Still, we managed to cross it at its shallowest point without submerging the bottom of the car.

Our fourth obstacle was a patch of rocky road full of dips and peaks. We jumped out of the car again, looking back and forth between the sharp rock edges and the Nissan’s small tires. Finally, Sheenal and Stacy mapped out a path for Gunnar to follow and guided him over the rocks. Gabi and I took videos from the sidelines.

Sunset had arrived. Despite the looming darkness, our confidence was increasing. We were doing it! We were going to make it through Route 40.

And then came the fifth obstacle: a small, rushing river. It was wide and deep with a healthy current. (As it turned out, a river to “them” was a river after all.) We got out of the car again, trying to determine the best way to cross. Surprising myself with a bit of bravery, I donned my waterproof sandals and waded to the center to determine the water’s depth. It was about halfway up my calf. Was that deep enough to submerge the bottom of the car?

The sun continued to set as we weighed our options. Gunnar decided that we should cross the river on foot while he drove through alone, in case the car bottomed out. Stacy found a way across by walking further down the side of the river and jumping over rocks. I waded to the other side, then took off my sandals and threw them to Sheenal. Once Sheenal was on the other side with me, we planned for her to throw my sandals to Gabi.

Then, everything came to a halt. “Guys, I actually think we should turn back,” Gunnar said.

We stared at him.

“It’s going to get dark pretty quickly. And if the car bottoms out, that’s it for us. We have no service out here. We also don’t know how many more rivers we’ll hit, or if we can get back across this one.”

It was like he had flipped on a rationality switch in my brain. I was on the side of a river in remote Argentina with no cell service and no food and no shoes! “I think you’re right. We should turn back,” I said. Gabi also agreed. Stacy and Sheenal initially protested but then decided Gunnar was right.

As we settled back into our assigned seats, Stacy requested upbeat songs from my iTunes. We still had no service, so we couldn’t research or call hotels. We had no food. We were below half a tank of gas. But it was nothing some nostalgic 2000s songs couldn’t fix. We sang along to “The Middle” by Jimmy Eat World, “Drops of Jupiter” by Train, and “Yeah!” by Usher. Several times, we pulled over to gaze at the crystal-clear array of stars. Things weren’t going well, but they were also going just fine.

Part V: Cachi and the Kissing Bugs

Three hours later and a half hour before midnight, we pulled into a village called Cachi. Gunnar’s eyes were bloodshot from driving, and our tailbones were numb. As we shook out our legs and looked around, we saw that the town was alive. The village center was decorated with twinkling string lights, and locals strolled up and down the wide, dirt-packed main road. A gaucho in all white sang and played guitar outside of a restaurant. He noticed us—five obvious tourists in dusty clothes—and propped up his guitar against a table. He walked over to where we stood.

“Tourists?” he asked. We nodded. He asked in broken English if we had a place to stay. We shook our heads “No.” He nodded and thought for a moment. Then, he beckoned for us to follow him.

“Where are we going?” I asked as we turned down a dark street. (Were we about to get murdered?) Sheenal shrugged, and we followed the gaucho up to a door. He knocked, and we waited. Eventually, a woman answered. The gaucho asked her a question and she shook her head no. He turned around, frowning. Then he raised a finger as if to say, “Ah! I know!” and beckoned for us to follow him again. We walked back into the town center and down another road. The gaucho stopped at one of the buildings and knocked on the door. Again we waited, and soon a woman answered. The gaucho spoke to her for a moment, then smiled and beckoned us inside.

As we stepped down into the entryway of the building, I felt as though something was wrong. The vestibule was clean, but it stank of mildew. “Aw, it smells like my dad’s old boat!” Gunnar said, smiling fondly. I looked at the others. They seemed…relaxed? Relieved? The woman and the gaucho turned left and walked us down a dark outdoor hallway. To our left, I saw a fluorescent kitchen area with a battered old fridge and a sink. To the right was a bathroom with no light, a dirty toilet, a moldy mop and a dripping faucet. Further down the outdoor hall, hostel guests were gathered at a wooden picnic table eating a late meal. The woman led us past several closed doors until we reached the very last door in the hall. She opened it and revealed a six-bed bunk room with one small window. Each green, plastic mattress had a set of folded, mismatched sheets and a single pillow. Everything smelled musty. The gaucho turned and spoke to the woman, who spoke to Gunnar.

“So, she says she can give us this room for 4,000 pesos each,” Gunnar said. That was roughly $4 U.S. dollars per person.

“That’s amazing!” said Sheenal.

“Perfect,” said Stacy. The woman picked up on the group’s excitement and relief (minus mine) and smiled warmly. She and the gaucho left, and we dropped our bags on the bunks. Another wave of anxiety washed over me as I noticed several bugs on the walls. Were they “kissing bugs,” the deadly insects my mom had told me about? Would I have to sleep here? And try to get ready for bed in a bathroom with no door and no light?

I silently followed the group out of the hostel and into the village center toward the only restaurant that was still open. My mind raced as we ordered food, and when our meals came, I silently chewed my strange, spiced spinach-and-cheese-filled manicotti (it was more of a spongy crepe) covered in a red tomato sauce.

“I think I might want to stay in the car tonight,” I said at last, trying to sound nonchalant. Even the fart wagon was better than our hostel room, I had decided.

Stacy looked up. “Why?” she asked. I launched into an explanation, highlighting the dirty bathrooms with questionable water, the stuffy room and the mildew smell. “And then, there were bugs on the walls, and I’m worried they’re kissing bugs,” I finished.

“What’s a kissing bug?” Gabi asked.

“My mom put it in my head and freaked me out,” I said. “They’re these bugs that hide in the cracks of clay houses in remote areas of South America. They come out at night and they bite you on the face, and if they poop near the wound you could get Chagas disease and die.” The group was quiet.

“I don’t think we’re in that remote of an area,” Stacy said gently.

“And I don’t think the walls in the hostel are made of clay. Probably concrete,” Gunnar added.

“Yeah, but they might be made of Adobe,” I said. “The dry mud brick stuff.”

“Do kissing bugs live in Adobe?” Sheenal asked. I did a quick Google search. A few websites confirmed that the bugs could hide in the cracks of Adobe homes.

I felt my biggest wave of anxiety yet. I was going to get bitten and pooped on later tonight and die from a parasitic infection two weeks later. Unless I accidentally ingested the hostel bathroom water and died from traveler’s diarrhea first. I wanted to go home!!!

The group tried to calm my fears during the rest of dinner. I couldn’t decide whether I should be brave, acknowledge my enormous privilege and tough it out for one night, or if I should abandon this crazy group of nomads and stay in the car, safe from the kissing bugs. No one wanted me to stay in the car, so Gunnar began calling and messaging hotels in Cachi via WhatsApp. But it was past 1 a.m. and he got no responses. We hopped back in the car and drove to two different hotels in town. Both were locked, with no one in the reception area.

Gabi argued that we should go back to the hostel. It was 1:45 a.m. now, and we would get no sleep. We at least had a place to stay. It was just one night. And so, I blocked out my internal scream and decided to tough it out. I told the group I was okay to sleep in the hostel, and that everything would (probably) be fine.

Gunnar drove us back to the hostel. We clambered out of the car and entered the building, and I reminded myself that this was no big deal. It was just one night.

We hadn’t even reached the outdoor hallway when Gunnar stopped us. He had just received a message on WhatsApp from one of the hotels. They had rooms available. Tonight! Gabi initially protested—it was so late—but our relief lessened her concerns. (My tale of the kissing bugs had had an effect after all.) We immediately turned around and left. The very nice woman who ran the hostel could keep our four dollars each!

By 3 a.m., we had three hotel rooms complete with white sheets, showers, big windows, and ceiling fans. The cost was about $25 U.S. dollars per person. As I settled into bed and closed my eyes, I decided it was the best $25 I had ever spent.

Part VI: Back To Salta

The next morning, we woke up to discover that our oasis of a hotel had free breakfast and a gorgeous view overlooking open fields and distant mountains. Stacy, Sheenal and I dug into sugar-crusted rolls, jam, ham, cheese, yogurt, juice and coffee while Gunnar drove to the local gas station. Gabi used the extra hour to sleep in.

After breakfast, we quickly packed up our things and headed to the front desk to check out. I felt my phone buzz and opened my WhatsApp. A new message from Gunnar induced a fresh wave of anxiety in my stomach: The gas station in town was out of gas. The refill truck wouldn’t arrive until 2 p.m. Would we stay in Cachi all day or drive back through the national park and get stuck on a mountain with no cellphone service?

By the time Gunnar found us in the lobby, he had a plan. We could make it to Salta by the skin of our teeth; we had just enough gas to reach the next gas station three hours away. (Suddenly, I appreciated the fart wagon and its low fuel usage.)

We drove out of Salta to the tune of Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again,” heading back to Route 33. We found a new interest in completing yesterday’s trek in reverse; it was sunny and clear, so every cactus and mountain was visible. When we reached Bishop’s Slope once more in Los Cardones National Park—I was still in the middle seat to ease my fear of heights—we stopped again to appreciate the view. Without the fog, we could see the entire valley below.

Further along Route 33, we decided we had the time (and gas) to explore another viewpoint. We stopped in Chicoana to buy more water and take pictures with llamas. Finally, we reached the end of the park and I felt the knot in my stomach unwind. We were back on flat roads heading into Salta, and we had cell service. When we finally pulled into a gas station, the gas meter was on E. We had made it by the skin of our teeth.

Back in the Salta city center, we found a traditional Argentinian restaurant for lunch. The restaurant was more of a small building with a kitchen and bathroom, and seating was in an outdoor courtyard. While the rest of us ordered items with which we were familiar, Gunnar ordered Locro Stew: a rich, Argentinian soup filled with beans, sausage, chives, mystery meats, and some sort of grain. I surprised myself by tasting it, carefully avoiding the tube-like mystery meat, and found it delicious. We also tried Salta beer, which was dark, rich and tangy.

During our meal, a caricature artist sat at our table and offered to draw us. He joked in Spanish as he worked, tossing out cheeky insults. The final result, which he revealed by unfurling the paper very slowly, was quite a liberal interpretation of our group. Gabi’s caricature had the smallest eyes I had ever seen, and all the girls were well-endowed. We laughed until our sides hurt, then paid the artist for his time. We decided that Gabi would be responsible for holding onto the cursed drawing.

Part VII: To the Salt Flats (and My Doom)

By now, it was time to hit the road. We were on our way to Salinas Grandes, or the Great Salt Flats, in Jujuy, Argentina, and then to our Airbnb in Purmamarca. The drive between Salta and Salinas Grandes was another four hours, so I handed the AUX cord to Sheenal for a change of music. The time passed peacefully, and Gunnar continued to drive despite Stacy’s offers to switch. Sheenal flew her drone outside the car window, capturing images of the jagged purple mountains to our left.

Eventually, we turned off of flat, straight Route 9 and onto winding Route 52, passing through Purmamarca on our way. The road began to curve left and right, making its way up mountains. When we reached the first hairpin turn, I held my breath, but then I released it. This would be a breeze. I had just gone through Los Cardones National Park twice.

I was very wrong. Each hairpin turn felt more perilous than the last. Every time the car curved around a bend without guardrails, I imagined us careening off the side. Closing my eyes only made the image more vivid. I gripped my right wrist tightly with my left hand, a move that helped more with motion sickness than pure terror, hoping it would still distract me from the sickening drop. My friends gazed out the windows appreciatively and took photos of the enormous red mountains and dark, far-away valleys below. We passed by several viewpoints but did not stop, as everyone wanted to make it to the salt flats by sunset. (I simply wanted to make it there alive.)

Up and up we went, and the switchbacks seemed to go on forever. We passed by an overturned semi-truck and I felt a whoosh of fear travel through my whole body. I squeezed my wrist relentlessly, heart fluttering, and willed our little fart wagon to reach the salt flats.

At long last, the road flattened out, and on either side of us was level ground. I quietly took deep, long breaths, willing my heart to slow down. We drove for another 20 minutes before we reached a barren welcome center. Three or four cars were already there with tourists waiting for sunset.

Stepping out of the Nissan and onto the salt flats felt like stepping onto Mars. It was icy cold, dry, windy and quiet. The honeycomb-like structure of the flats extended far beyond what we could see.

The wind whipped my hair back and forth into a wild frizz, and I tugged my thin windbreaker over my shoulders. We marveled at the vastness and emptiness in every direction, taking photos and videos of ourselves as we ran, jumped and laughed. We watched as the sun slipped below the horizon, leaving behind a buttery orange glow.

When the last of the sun had faded and we had all taken pee breaks behind a tiny brick building, we got back into the car and relished the instant lack of wind. It dawned on me that I would have to face the cliffside mountains yet again, but this time in darkness.

And so, dear reader, we have finally reached the scene of my harrowing nightmare. After all the false death alarms from the past few days, driving down the mountain from the salt flats was when I truly thought I would die. A vision of the car skidding out and flying into the valley of blackness played out in my head during every hairpin turn. I squeezed Gabi’s shrimp pillow and let my anxiety run rampant, energy coursing through me. But no matter how awful the scene became outside the cracked windshield, I couldn’t tear my eyes away. I cried all the way down the mountain.

When we finally reached flat ground, I sniffed quietly and dabbed my face with my sleeve. I felt my body unwind and immediately became exhausted.

“Are you okay?” Gabi asked 20 minutes later, turning to look at me. I smiled weakly. “Yeah,” I said.

“What do you mean?” Gunnar asked.

“Jenna’s been crying,” Gabi said.

“Crying?” Stacy said, whipping around to see my face.

Sheenal turned to look at me. “I didn’t even notice!”

“Neither did I!” said Stacy.

“Wait, you were crying?!” Gunnar asked.

“Yeah,” I said, starting to laugh.

“From what?”

“The mountain.”

“The mountain?”

“Uh, yeah. I thought I was gonna die.”

“You don’t trust my driving skills?!”

“That’s kind of scary that you can hide it that well,” Stacy said.

“How didn’t you notice her crying, Sheenal?! She was right next to you!” Gunnar said.

Everyone laughed as I explained my fear of heights in more detail, and the group continued to marvel at my silent crying skills.

By the time we reached Purmamarca, I was exhausted and emotionally shot, but happy. At long last, we had made it to our Airbnb. We hadn’t been robbed, murdered, bitten, pooped on, or found in a car wreck at the bottom of a valley. In every town we had visited, the locals were warm and kind. The roads we had traveled were some of the most beautiful I had ever seen. And of course, I had four new friends who didn’t mind that I was a novice traveler, who were patient and willing to put up with my intense anxieties.

My fear of heights was never cured—we drove up another mountain the next day after Gunnar had told me there were no more mountain roads, and I imagined chucking the shrimp pillow at his head—but I had learned that it didn’t have to limit me. I could still travel and do cool things, knowing I would come out the other side happy that I did.

Below is the Salta Road Trip story told by Jenna in her own words.

After reading, you can watch the full Salta Road Trip Video here.

Notice the difference in emotion... Enjoy.

Jenna Cartusciello is a writer and editor based in New Jersey. Her favorite travel memories include eating a peanut butter and jelly at the highest Matterhorn viewpoint, performing an impromptu three-minute dance on an ancient stage in the Palace of Knossos, Crete, and jogging down a steep road with a belly full of pasta and wine to catch the last train home in Orvieto, Italy.

(Photo taken in Cardones National Park, Salta, Argentina)